Difference between revisions of "Isaac Asimov"

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

==Personal Life== | ==Personal Life== | ||

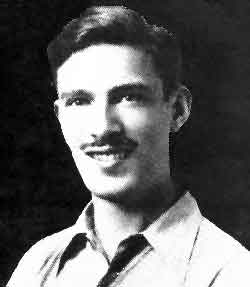

[[File:AsimovGertrude&Isaac.jpeg|thumb|'''Gertrude and Isaac.''' ''Photo by [[Jay Kay Klein]], from the collection of [[Frederik Pohl]].'']] | [[File:AsimovGertrude&Isaac.jpeg|thumb|'''Gertrude and Isaac.''' ''Photo by [[Jay Kay Klein]], from the collection of [[Frederik Pohl]].'']] | ||

| + | Asimov was born in Petrovichi, Russia, on an unknown date between October 4, 1919, and January 2, 1920. He celebrated his birthday on January 2. He emigrated to New York as a young child. He got a Ph.D. in Biochemistry and became a professor at Boston University. He had hoped to be a doctor, but could not get admitted to medical school because of [[racism|antisemitism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Asimov met his first wife, Gertrude “Gittel” Blugerman (1917–1990), on a blind date on February 14, 1942, and married her on July 26 the same year. They had two children, David (born 1951) and Robyn Joan (born 1955). Asimov had many extramarital affairs, and the couple divorced in 1973 after a three-year separation. He married [[Janet O. Jeppson]] on November 30, 1973, two weeks after his divorce became final. | ||

| + | |||

Asimov wrote three [[autobiographies]]: ''In Memory Yet Green'', ''In Joy Still Felt -- The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954–1978'', and ''[[I. Asimov]]''. The first two are detailed accounts of his life, while the last is an engaging series of small essays on people and things that mattered to him. | Asimov wrote three [[autobiographies]]: ''In Memory Yet Green'', ''In Joy Still Felt -- The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954–1978'', and ''[[I. Asimov]]''. The first two are detailed accounts of his life, while the last is an engaging series of small essays on people and things that mattered to him. | ||

| Line 31: | Line 35: | ||

<blockquote>On meeting an attractive woman — one who was not obviously the Most Significant Other of some male friend — he was inclined to touch her … not immediately on any Off Limits part of her anatomy but in a fairly fondling way. (When I called him on it once, he said, "It's like the old saying. You get slapped a lot, but you get laid a lot, too.")</blockquote> | <blockquote>On meeting an attractive woman — one who was not obviously the Most Significant Other of some male friend — he was inclined to touch her … not immediately on any Off Limits part of her anatomy but in a fairly fondling way. (When I called him on it once, he said, "It's like the old saying. You get slapped a lot, but you get laid a lot, too.")</blockquote> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=='''More information:'''== | =='''More information:'''== | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

*{{link | website=https://youtube.com/watch?v=OAxlrdkY1oQ | text=Talk at Boskone 5.}} | *{{link | website=https://youtube.com/watch?v=OAxlrdkY1oQ | text=Talk at Boskone 5.}} | ||

*{{SFE|name=asimov_isaac}}. | *{{SFE|name=asimov_isaac}}. | ||

| − | * [[Frederik Pohl]]’s reminiscences of Asimov from [[The Way the Future Blogs]] (archived): [ | + | * [[Frederik Pohl]]’s reminiscences of Asimov from [[The Way the Future Blogs]] (archived): [https://web.archive.org/web/20110208012848/https://www.thewaythefutureblogs.com/2010/01/isaac/ Part 1,] [https://web.archive.org/web/20101026204916/https://www.thewaythefutureblogs.com/2010/01/isaac-part-2/ Part 2,] [https://web.archive.org/web/20101114033837/https://www.thewaythefutureblogs.com/2010/02/isaac-part-3-of-quite-a-few/ Part 3,] [https://web.archive.org/web/20101114124828/https://www.thewaythefutureblogs.com/2010/02/isaac-part-4-and-some-other-guys/ Part 4, ][https://web.archive.org/web/20101114124914/https://www.thewaythefutureblogs.com/2010/03/isaac-part-5-in-our-continuing-series/ Part 5,] [https://web.archive.org/web/20101114150357/https://www.thewaythefutureblogs.com/2010/11/isaac-asimov-part-6/ Part 6,] [https://web.archive.org/web/20101119094216/https://www.thewaythefutureblogs.com/2010/11/isaac-asimov-part-7/ Part 7.] [https://web.archive.org/web/20100728090610/https://www.thewaythefutureblogs.com/2010/06/russians-jews-and-isaac/ Russians, Jews and Isaac.] |

{{recognition}} | {{recognition}} | ||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

* 1966 -- [[Lunacon 9]] | * 1966 -- [[Lunacon 9]] | ||

* 1967 -- [[Skylark Award]], [[Isaac Award]] | * 1967 -- [[Skylark Award]], [[Isaac Award]] | ||

| + | * 1970 -- [[Toastmaster]] at [[1970 Open ESFA]] | ||

* 1972 -- [[Star Trek Lives!]] | * 1972 -- [[Star Trek Lives!]] | ||

* 1974 -- [[Boskone 11]] | * 1974 -- [[Boskone 11]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:11, 31 May 2024

(ca. 1920 – April 6, 1992)

Isaac Asimov (sometimes, to his displeasure, called Ike) was an early fan and a famous pro.

Beginning as a reader of the pulps -- his father gave him the first issue of Science Wonder Stories at age 9 -- he was soon letterhacking. Isaac Asenion, a misspelling of his name in the prozine letter columns when he was an unknown fan with a strange name might count as a penname. (Paul French was an actual pseudonym Asimov used for the Lucky Starr series of YA novels.)

I. Asimov, his autobiography, won the 1995 Best Non-Fiction Book Hugo.

Contents

Fan[edit]

He was introduced to fandom by Jack Robins and became a member of the Futurians, but was a bit too young to take part in their ferocious politics. He attended the First Worldcon, but was not active enough in the Futurians to be excluded. (See Exclusion Act.)

While living in Boston, he was a member of NESFA. (He was fannish enough to figure in the story of a certain fan-turned-pro's visit to a NESFA meeting where IM, the clubzine, was being collated. The neopro, asked to help collate, loftily replied that as a pro he no longer did such things. Just then, Ben Bova came out from another room and said, "Do you have any more page 6? Isaac and I are out.")

He spoke fluent limerick and was easily able to extemporize. He was Worldcon toastmaster at Pittcon, Detention, Tricon, Discon and Philcon II. He was afraid of flying, which greatly limited his travel.

Pro[edit]

The start of Asimov's writing career was part of the Golden Age of Astounding inaugurated by John W. Campbell and during the 1940s, Asimov wrote some of his most famous short fiction, including the original Foundation and Robot stories, including publishing the Three Laws of Robotics. In the ’50s, he turned to novels and then mostly to non-fiction. He was a long-time science columnist in F&SF.

During his lifetime, he wrote over 500 books and many tens of thousands of letters and postcards.

He was a member of the Trap Door Spiders, and the discoverer of Thiotimoline. He gave his name to Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine and helped to guide its early years.

Personal Life[edit]

Asimov was born in Petrovichi, Russia, on an unknown date between October 4, 1919, and January 2, 1920. He celebrated his birthday on January 2. He emigrated to New York as a young child. He got a Ph.D. in Biochemistry and became a professor at Boston University. He had hoped to be a doctor, but could not get admitted to medical school because of antisemitism.

Asimov met his first wife, Gertrude “Gittel” Blugerman (1917–1990), on a blind date on February 14, 1942, and married her on July 26 the same year. They had two children, David (born 1951) and Robyn Joan (born 1955). Asimov had many extramarital affairs, and the couple divorced in 1973 after a three-year separation. He married Janet O. Jeppson on November 30, 1973, two weeks after his divorce became final.

Asimov wrote three autobiographies: In Memory Yet Green, In Joy Still Felt -- The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954–1978, and I. Asimov. The first two are detailed accounts of his life, while the last is an engaging series of small essays on people and things that mattered to him.

Under the not very secret pseudonym "Dr. A.," Asimov wrote The Sensuous Dirty Old Man; it was meant as a joke, but many femmefen could attest to Asimov's wandering hands and blatant propositions. His lifelong friend Fred Pohl recalled:

On meeting an attractive woman — one who was not obviously the Most Significant Other of some male friend — he was inclined to touch her … not immediately on any Off Limits part of her anatomy but in a fairly fondling way. (When I called him on it once, he said, "It's like the old saying. You get slapped a lot, but you get laid a lot, too.")

More information:[edit]

- Early short biography in Who's Who in Fandom 1940, page 3. (He was called "An up-and-coming young writer who'll go places and do things.")

- Video of interview by Simon Borden.

- Video of tribute at MagiCon.

- Talk at Boskone 5.

- Entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

- Frederik Pohl’s reminiscences of Asimov from The Way the Future Blogs (archived): Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7. Russians, Jews and Isaac.

Awards, Honors and GoHships:

- 1955 -- Clevention

- 1966 -- Lunacon 9

- 1967 -- Skylark Award, Isaac Award

- 1970 -- Toastmaster at 1970 Open ESFA

- 1972 -- Star Trek Lives!

- 1974 -- Boskone 11

- 1975 -- Star Trek Lives!

- 1976 -- Balticon 10, Fellow of NESFA

- 1979 -- Future Party '79

- 1981 -- Disclave 25, URCON III

- 1982 -- SF Con V

- 1983 -- I-Con II, Empiricon 4

- 1985 -- Triangulum 1985

- 1986 -- Philcon 1986

- 1987 -- SFWA Grand Master Award

- 1990 -- Forry Award

- Two Nebula Awards for fiction

- Six Hugos: 1966 Best All Time Series Hugo, 1973 Best Novel Hugo, 1977 Best Novelette Hugo, 1983 Best Novel Hugo, 1992 Best Novelette Hugo, 1995 Best Non-Fiction Book Hugo, as well as the 1946 Best Novel Retro Hugo in 1996, the 1941 Best Short Story Retro Hugo in 2016 and the 1943 Best Novelette Retro Hugo in 2018.

- Hugo nominations: 1956 Best Novel Hugo, 1975 Best Novelette Hugo, 1980 Best Non-Fiction Book Hugo, 1981 Best Non-Fiction Book Hugo, 1984 Best Novel Hugo, 1987 Best Short Story Hugo, 1996 Best Non-Fiction Book Hugo, 1946 Best Novella Retro Hugo in 1996, 1951 Best Novella Retro Hugo and 1951 Best Novel Retro Hugo in 2001, and 1954 Best Novel Retro Hugo in 2004.

Major Works[edit]

U.S. Robotics/Susan Calvin series[edit]

Collected in the fix-up I, Robot.

Laws of Robotics[edit]

| From Fancyclopedia 2, ca. 1959 |

Laws of Robotics One of the real inventions in the field of stfantasy. The laws worked out by Isaac Asimov in his US Robots and Mechanical Men (aka Positronic Robots, and Susan Calvin) Series declare

Others have also developed the idea, if not in just this form then at least as a definite set of built-in laws of robotic behavior whose consequences are fictionally explored. |

| From Fancyclopedia 2 Supplement, ca. 1960 |

| These were actually suggested by Campbell, Asimov having merely suggested that they existed. |

According to Asimov, he did not originate the Laws, but was given them by John W. Campbell, who said: "Go and write stories based on this!". He did coin the term robotics, though, in his May 1941 Astounding story, “Liar!” Although foreshadowed in this story, the “Three Laws” were first spelled out in “Runaround” (Astounding, March 1942).

Foundation Series[edit]

Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy consists of three books:

- Foundation

- Foundation and Empire

- Second Foundation

The Foundation series, of which the trilogy is the main part and the first to be written, was written over a span of 44 years. The series consists of seven volumes that are closely linked to each other, although they can be read separately.

The series is highly acclaimed. It has had a wide influence in fandom (probably only exceeded by The Lord of the Rings and E. E. Smith’s Lensman series) with many clubs and fanzines being named from it:

- Seldon's Plan

- Wayne Third Foundation

- Foundation

- Third Foundation

- Second Foundation

- The Return of Seldon

Awards and Honors

- 1966 Best All Time Series Hugo (a one-time Hugo category)

| Person | 1920—1992 |

| This is a biography page. Please extend it by adding more information about the person, such as fanzines and apazines published, awards, clubs, conventions worked on, GoHships, impact on fandom, external links, anecdotes, etc. See Standards for People and The Naming of Names. |